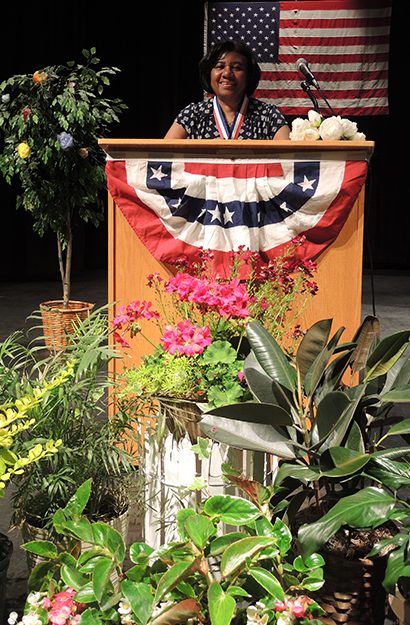

Pamela Lewis – 2017’s Greatest American Thinker!

Had he lived during the 2016 presidential election, Pontius Pilate might have asked his famous and mocking question, “What is truth?” For me, as well as for many of my fellow Americans, the campaign raised questions not only about the candidates, but about the nature of truth itself.

Had he lived during the 2016 presidential election, Pontius Pilate might have asked his famous and mocking question, “What is truth?” For me, as well as for many of my fellow Americans, the campaign raised questions not only about the candidates, but about the nature of truth itself.

From the time when I first voted, in 1971, until 2012, I had always been confident that the candidates who were running for president, and that the media responsible for and dedicated to informing the electorate were committed to truth. Regardless of what I thought of the candidates’ platforms and positions on the issues of the moment, I never questioned nor struggled with my perception of truth. I held up the candidates’ competency and their policies for scrutiny; listened attentively to the points they raised in debates; and I made every effort to learn about the important issues by reading and listening to trusted newspapers and broadcasts, whose reporters were trained professionals with proven expertise. While I may have disagreed with what I garnered from those sources, I never felt that my perception of what was true had been compromised.

I have noted a marked difference between the elections of those earlier eras and that of 2016 as regards the dissemination of news. Whereas we received our news from journalists and reporters with expertise, as I noted earlier, in the 2016 election, reporting has come from pundits, manipulative speakers, and an expansive network of social media. In this last election cycle, I felt assailed and overwhelmed by the large amount of information, all claiming to have the “truth” about the candidates and their positions. Of course, I could have simply turned off my radio and television, and called a moratorium on reading the newspaper until the election had ended. But that would not have been an intelligent or realistic solution to that problem. Instead, I chose a couple news sources I deemed consistently trustworthy and unbiased and based my opinions on their content. I learned to be more selective and discerning.

Regardless of party affiliation, the candidates frequently bombarded us with empty, sincerity-glutted rhetoric. While this tactic was designed to make the speakers’ comments “resonate” with us, for me it had the opposite effect in that I felt manipulated and patronized. The constantly stated claim that “the system is rigged,” or that the opposing candidate’s supporters are “deplorables,” did not help me as a voter to make an informed choice. There were no facts, there was no truth, except that which came from the perspective of the candidate making the damning claim. Classic, well-constructed rhetoric is in the service of truth because it is founded on facts.

Another obstacle to perceiving truth was the emergence of “fake news,” a term that was unheard of when I first began voting. While it may sound amusing at first hearing, I saw this oxymoronic phenomenon as a threat to our democratic life and contrary to how a free nation gathers and provides information to its citizenry. I consider “fake news” as one of the darker aspects of social media, where many participants create and manipulate events to purposely deceive readers. Like others who have been taken in by this problem, I had also been deceived by inaccurate information.

My perception of truth occurs through experience and through the opportunity to access and analyze facts. When facts are corrupted or withheld outright, it becomes impossible to perceive truth; it becomes difficult to engage in reasoned discussions with others. If I distrust the facts, I am thereby unable to trust anything, and then the only truth that counts is my own, which cannot be considered the ultimate truth.

I found it very difficult to maintain my perception of truth during the 2016 election, given the various ways I have cited in which facts were tampered with, as well as due to the manipulation of language in the form of bad rhetoric. Although I believe to have cast my vote for the most worthy candidate, I would have preferred to have done so without my perception of truth having been changed.

Nancy Krier – 2nd Place

After the 2016 election, I marched in Washington, D.C. with half a million people, including my friend and her nine-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. A group near us chanted, “Science is real! Science is real!”

After the 2016 election, I marched in Washington, D.C. with half a million people, including my friend and her nine-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. A group near us chanted, “Science is real! Science is real!”

Why were they chanting? And why did I fly in the January cold from one Washington to the other to join the historic Women’s March? The reason: the 2016 election and the attempts to change our perception of truth.

Did the election successfully change our perception of truth? No. We still know what truth is. Real truth is grounded in real facts.

However, the election starkly reminded us that we need to defend that perception. As an attorney and former journalist, I believe that real facts — like a real Minnesota blizzard — can be observed, documented and verified.

And then, the real truth arising from those real facts must be made public.

The 2016 election bombarded us with unverified and false statements — troublingly referred to now as “alternative facts.” We know alternative facts are not real. We know false prophets never lead to truth. Abraham Lincoln once said he had faith in the people, but there is danger when they are misled. “Let them know the truth and the country is safe,” he instructed. Today, Lincoln would explain that denying verified climate change data can never lead to truth about our planet’s future. He would deplore attempts to spread “false truths” seeking to deceive the nation.

As alarmed as I am to be subjected to such attempts, the 2016 election’s propagandizing may unintentionally benefit democracy. The disinformation has propelled me and so many others to become more clear-eyed, robust and organized in our insistence on real facts and real truth.

That consequence is a timely lesson. Sometimes we forget that we have trudged this painful road before. In the Declaration of Independence we announced, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” In other words, we proclaimed that England could not justly rule us without embracing these basic facts, our known truths. But it was critical that we say so openly, and then fight. We could not take our perception of truth for granted.

In our self-governance since then, we have repeatedly fought for real facts and thus real truth. We did it during McCarthyism, Vietnam, and the Iran-Contra Affair. I saw this when I became a reporter not long after Watergate, a time we demanded real facts because we suspected our President was lying. As I write this essay it is national Sunshine Week, recognizing laws guaranteeing our access to information. How fitting. At bottom, when democracy is in trouble, we the people publically insist on real facts and real truth in order to maintain control over the instrument we created: our government.

It is no different now. The 2016 election requires us once more to protect our perception of truth, especially with today’s technology. The 24-hour incessant drumbeat of phony statements on TV, websites and social media threatens to confuse, overwhelm and exhaust us. But Franklin Roosevelt said repetition does not transform a lie into a truth. So, we hold fast in our perception that the real truth requires real facts, no matter how furiously false information is tweeted, or how repetitiously real facts are denied. This effort is not easy for us. Democracy rarely is.

After marching in D.C., my friends and I stopped into a museum that celebrates the First Amendment’s five freedoms: religion, speech, press, assembly and petition. The museum displays daily newspapers’ front pages. Reading those, I was sadly reminded that many traditional media struggle financially and may not survive. I have taken for granted that professional reporters would always uncover the real facts, enabling us to establish the real truth. But those days are waning. This reality, coupled with the speed at which information races at us, means we can no longer solely rely on professionals to sift real news from “fake news.” We must become our own fact-checkers, our own truth-tellers, essentially, our own journalists. Luckily, we can do this. We, too, can tweet.

To paraphrase a famous editorial, yes, Elizabeth, science — like climate change — is real. So is equality for women and other irrefutable rights. These are today’s real facts, indivisible from real truths. The 2016 election did not change that perception.

So, we march.

Kris Pauna – Finalist

The 2016 election changed our perception of truth, or at least our perception of Collective truth.

The 2016 election changed our perception of truth, or at least our perception of Collective truth.

Reflecting on “truth” and the 2016 elections creates a paradigm that may have never existed before. What many people saw as truth about each of the major presidential candidates would have disqualified those candidates from office in other years. We heard countless times it was a choice between the lesser of two evils.

How could this new paradigm exist? A system where the animosity people held for one of the candidates was offset by unbridled passion for that same candidate by their neighbors. A system where each candidates negatives in polls outweighed their positives, where they were, at both times, messiahs and heretics.

Truth, or what is true, is simply something that is in accordance with the facts. Facts are just information or data which requires an interpretation and that interpretation is often rooted in a set of experiences and beliefs. This means truth is not static, it is an interpretation of the world seen through out personal lenses. As a result people form a subjective truth, or what they believe based on the information presented and interpreted by themselves. An example is whether God exists. As people look at the facts presented to them, they interpret those facts through their individual lens and form a subjective truth about God.

As social creatures, once we form our subjective truth we test it with our friends, family, neighbors, and community. This further melds our subjective truth as we likely drop some of the most extreme interpretations of facts and adopt more moderate views. Things that were true through our own personal lens that aren’t validated by our community and, of which we cannot easily defend, are dropped while those interpretations that are collectively held are confirmed. This Collective truth is what holds communities together and confers as sense of belonging on the members of those communities.

In the 2016 election the forming of a Collective truth morphed into the social media realm which dramatically changed our perceptions of truth. Where once people sought Collective truth in their literal communities, they can now turn to the anonymity of the internet to find that same sense of belonging. These online communities don’t have to follow existing social norms, and since you likely will never meet the people on the other side of the screen, you don’t have to worry about the ramifications of insulting them. As a result, these online communities can hold extreme views and when faced with facts can interpret them in the most extreme light and their members will gain validation by the community all hidden in a veil of secrecy.

So, as we look at a fact like, Hillary Clinton used a private email server, these online communities interpret that fact through an extreme view and conclude that either she committed a crime and should be locked up, OR it was no big deal because no classified information was ever sent or received and there was no evidence the server was hacked. When Donald Trump bragged about assaulting a woman and women came forward corroborating that his behavior matched his words, we again interpret those facts to conclude he was bragging and it was “locker room talk” and the women were fame seekers OR we interpret those facts to conclude that he has a history of sexually assaulting women.

To further compound the issue we moved into a world where facts are no longer just open to interpretation, they are open to creation. Even the president and his aids have used alternative facts to cloud the discussion. When faced with concrete evidence that something isn’t true the administration now refutes that evidence and paints it as biased. To further complicate the issue the administration and the president make assertions that their alternate facts were widely covered by the media so they are just merely referring to media sources as the purveyors of these created realities. The problem is the sources being relied on aren’t the mainstream media which follows ethical levels of journalistic integrity, they are fringe outlets that exist to foster political conflict and division and create profits on social media through the exploitation of online communities.

It isn’t hopeless though. As we go forward we must be careful not to give our Collective truth away to social media trolls and profiteers. We can reclaim this great democracy if we are willing to shutdown our computers and sit down with our neighbors.

David Shapiro – Finalist

No, our perception of truth has not changed.

Truth is still perceived, as it always has been, as something like a correspondence with reality. It is still aspired to, an ideal we aim for in life’s most important pursuits. Truth is still distinguished from falsity or error, and no one is suggesting a new perception of truth when it comes to say, the truth of metal fatigue tolerances on the wings of jet airplanes they fly in.

What has changed is not our perception of truth, but the value we place upon it. Historically, truth was, as Emerson put it, “the foundation of the social state.” Our leaders were expected to speak the truth; doing so was considered a sacred duty. Politicians who lied (that is, who were caught lying) could expect to find themselves booted out of office, or at least, being required to give a very public apology for their mendacity.

In the wake of the 2016 election (and the long run-up to it), however, it seems to matter less whether someone speaks the truth just so long as they can persuade people to believe them.

This, of course, is not unprecedented. For instance, my dear departed mom, quoting the humorist Mark Twain, always used to say, “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story,” at which point she would launch into a rip-roaring yarn featuring some minor foible of her children exaggerated into epic hilarity.

Like when I was six and Duncan Wilcox dared me to stick my finger in the garter snake’s mouth. Naturally, it bit down and I ran home crying. Mom famously would regale her audience with the call she made to the pediatrician: “Do you think we need a physician to examine his finger?” she claimed to have asked. “No,” was the alleged reply from the good Dr. Mermelstein, “I think you need to have one examine his head!”

Naturally, this wasn’t exactly true, but it did give a very accurate account of both the tone of my youthful indiscretions and the typical sort of responses Mom had to them. The facts were off-target, but the meaning was spot-on.

So perhaps while truth remains the same idealized notion as ever, it’s belief that has changed. Ask yourself: can I believe in something I know isn’t true? Can I believe, for instance, that 2 plus 2 is 5? Probably not, but can I believe that it’s more than four if my political party’s candidate says so? Maybe, especially if that answer is tweeted and re-tweeted millions of times making me forget what the original question was in the first place.

P.T. Barnum’s observation that there’s a sucker born every minute doesn’t mean that women are pushing out to new dupes every sixty seconds; it means that every minute of every day another of us becomes an easy mark for an enterprising Barnum to prey upon. And the thing is, what we’re suckers for is the truth! Or at least, what we think to be true.

If I’m hitting you up for some money, it’s much more effective if I tell you truth: I’m an orphan, out of work, a victim of crime while serving our country than that I make something up. Conveniently leaving out the fact that I’m sixty years old, on summer vacation from teaching, and that the crime—a stolen wallet—happened forty-five years ago when I was working as a volunteer census taker doesn’t make me a liar, does it?

You see, truth is still the currency we trade in; it may just be that the currency has been devalued. In the past, truth could buy you great things: a cure for polio, a trip to the moon, a society based on rule of law; now, it can’t even stem the progress of human-induced climate change, unless, perhaps, it could convince people that climate can be made great again.

Nevertheless, I would contend that our perception of truth continues to be essentially the same as ever. The fundamental truths abide: it is still true that parents should love their children with all their hearts; still true that compassion ultimately defeats hate; still true that as Martin Luther King said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice;” and, of course, still true that at any potluck supper in Minnesota, you can always count on hotdish with cream of mushroom soup and tater tots.

That’s the whole truth, so help me God.